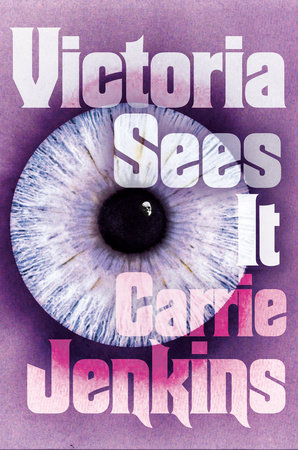

Carrie Jenkins is a public philosopher, scholar, and author of two books, What Love Is and What It Could Be and Victoria Sees It.

In March 2021, a few weeks before the release of her novel, I had the chance to speak to Jenkins over Zoom. She said something striking in our conversation which I still think about often today: “There’s a sense in which the only way that I can know the characters is via my sense of who and what they are.”

The idea that a character might be in some ways unknowable to their own novelist is a fascinating perspective on literature. It goes beyond typical “death of the author” criticism into an implicit proposition that the character might have its own soul, private from its creator. An author’s choices and perceptions shape a character’s reality. But between the lines of unconsidered behaviours and habits is a whole other, smaller life that plays itself out in small pieces to the book’s other readers. Something about this framework feels beautiful, to me.

Jenkins speaks with an unassuming manner that belies the vibrancy and remarkable cohesion behind her philosophies. I still come back and read this interview once in a while to spend more time considering her thoughts on writing, love & madness. It was a delight to speak to her about her work; I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did.

A version of this conversation appeared in The Puritan in August 2021.

In the second half of Victoria Sees It, Victoria recounts Humberton as saying that “the base layer of truth is what matters, even in fiction. You can make up whatever else you want, but if you lose sight of that fundamental level, the basement of your world, everything you build on top of it is wrong.” What would you consider the base truth of Victoria Sees It that you want readers to take away? Has the base truth changed over your revision process?

I think the one of the central ones is this gendered take on an individual's struggles with mental health, and the risk that that person is not seen. And that her story is not heard. And that she is not understood, so we get this very isolated viewpoint. There's a deeply gendered and classed aspect to her isolation that intersects with her attempts to thrive in an environment where she is just not very welcome. She doesn't get on very well, in academia, socially speaking; she doesn't really have any friends in her personal life either. There's something I'm trying to say about the way that Victoria is able to see things that other people cannot or will not see and understand them in ways that other people can't or will not understand them. But it would be very easy to dismiss her as being crazy. And I'm hoping one of the ways I'm hoping for this book to resonate with reality is in its exploration of madness, and especially women's madness, the insights or the wisdom that can sometimes be contained within that.

I’m interested in how that relates to the title of your novel, and how the motif of eyes and seeing is such a major part of Victoria Sees It. What was the process that you went through when titling the book, and what does it mean to you in the context of the novel?

The title came quite late in the day. It was working under various titles for a long time. And actually, I think when I originally sold the manuscript, it had a different title. And so it was quite a late stage development. There are lots of ways in which I think [Victoria’s] perspective is missing pieces: she misses lots of clues about her social environment, for example. For readers, it's easy to sort of see some things that Victoria doesn't see. And the title came out of a lot of discussions with my editor Haley Cullingham, who is absolutely amazing and has really understood this book in ways that I don't even understand. So that was part of where the title came from. One of the major things here is that Victoria sees things that are really there and are really true. But she's not able to communicate with them, and she's not really able to process them.

What were the initial names for Victoria Sees It?

For a while it was called Invariants, because one of the book's preoccupations is with how things can change over time while still remaining the same in essentials, and I was thinking about topology as a metaphor for this. So you can stretch or squish a torus in lots of ways, say to make it into a coffee mug or a long tunnel. But it will still always have certain topological properties, which are also called invariants, unless you actually tear the fabric it's made of. The metaphor is still in the book, just not in the main title. It's in the titles of each section: corridors, worms, donuts, et cetera. Worms are structurally a kind of digestive tunnel. So are humans! In a topological sense they're the same as a donut or a corridor. That's also why the last section is called "Tears:" I named it after the idea of tearing something, as in doing what you need to do to break away from those invariant properties. Not tears as in crying, although I do like that ambiguity.

It’s interesting that you mention your editor as knowing the book better than you do – it reminds me of a monologue when the italicized narrator says: “You think you know someone but it’s always you. Whatever you think someone is, like if you try to guess what they feel like you’re only imagining what you’d feel like.” Do you agree with their assessment of the limitations in knowing others?

That is such a great question. Yes, they feel to me like there are things about them that I don't know. There's a sense in which the only way that I can know the characters is via my sense of who and what they are. But I think that when other people read the same book, I think they will find different things out about the characters. And that includes ones that I can't really know for myself, or that I'm not able to access, because they're coming out of a subconscious region that I don't have access to. I think other people like Hailey, my editor, can sometimes see what's going on there more clearly than I would be able to. The process of reading and understanding what's on what's going on with the characters requires more than just my input. It's more than just writing it.

I couldn’t help but notice that Victoria Sees It follows the trajectory of your own life quite closely. You both studied philosophy at Cambridge, pursued careers in academia, and moved to North America to become professors. Can you speak to the elements of autobiography in the novel? How closely did you intend for Victoria to resemble you?

It's partly out of convenience. Because if she has been to the same places I've been to, then I know what they look like, and smell like, and sound like: who else is around. In a lot of ways the places and times that I was familiar with, which come out in Victoria's trajectory, seemed to me to be full of potential for storytelling. I've been in that library, for example, where there's a Winnie the Pooh manuscript next to Isaac Newton's notebooks. How could I not bring that up? These places are so rich, they kind of wrote parts of the novel into being for me, just by letting Victoria follow me around into those places where I've been. Obviously, many of the things that Victoria experiences are not things that have truly happened to me. But some of them I think, are the sorts of things that might have happened to me and not very different trajectories of my life. So some of my sort of twisted, subconscious alter ego fears get projected onto her certainly. This was another one of those things where I had to kind of trust my subconscious to do Victoria. Without worrying too much about “is she too like me? Is she too unlike me, is she too unrealistic, or too realistic?” I kind of had to just trust and write and see who she would be by the end of that. It didn't exactly feel like creating a character from scratch, because I had a lot of outlines of, you know, where she was going. But the line when she came into being, “my mother stopped talking when I was born,” that’s her. So she's always had a bit of independent identity there.

Your scholarly work partially centres around your thoughts on the philosophy of love, and it's the topic of two of your other books. What's Victoria's relationship with love? Do you believe she loves anyone in this story? Does anybody love her?

Oof. Yeah. I think she loves Deb, and I think Deb loves her. Beyond that: no, I don't think they do. Victoria is clearly attracted to The Cop, and vice versa, but she is kind of using her to find Deb. The Cop might be trying to love Victoria but she certainly doesn't know how to. They don't really succeed in knowing each other. And I certainly don't think anyone from Victoria's family shows her love. The aunt shows some care, but I'm with bell hooks in thinking love is much more than just care. And, in fact, that love is quite rare.

In your opinion what makes love genuine and distinct from obsession, admiration, attraction, and so on?

The more I think about this, the more I'm coming to think that attention is crucial. Paying attention to something or someone as they really are seems to be a really important part or precondition of loving them. And one of the things that's kind of brutal about what happens to Victoria is that except for Deb nobody gives that kind of loving attention to her. Not to her as she really is. A lot of the book is about the things that Victoria is being taught, and the information she receives. It’s not always clear how seriously the reader should take the lessons that have been imparted upon her. What parts of her education do you consider to be accurate reflections of your own mindset and pedagogy, and what do you think should be taken as a representation of academia’s systemic flaws? The true answer is that they're all just kind of messed up together. Some things I wouldn't ever dream of ever telling a student, some things that I might talk through with people that I was trying to learn with. A lot of what she is taught is not helpful to Victoria. And it would probably be better if she had more useful and kind teachers, and more empathetic, people more capable of understanding how she works. It's part of her trouble, that nobody else really understands how she works, and she doesn't really try to tell them either. There's a way to sort of break out of that situation, but she doesn't get what she needs. She gets intellectual training that she's able to use as anaesthetic so that she doesn't have to face reality in some respects. So she learns a lot of bad lessons. But some really interesting and really important, true or, at least, you know, as true as I would know, how to understand things as well in amongst the mix. And the problem that she faces is she has no handle on which is which. Part of what she's left vulnerable to is that she doesn't have a filter mechanism to know who to trust or, or what to hold onto as the truth.

That mix of lessons that are true and untrue seems like a point of nuance that’s very unique to novelistic writing. You’re coming in with a background as an academic writer, a public philosopher, and even a comic illustrator. For you, what was it about the novel as a genre that allowed you to express yourself in a way that you couldn’t with the mediums you’ve traditionally used?

I think a combination of two things. There’s the way that I'm able to let characters’ voices go to town. They can just go and go for 300 pages. In this case, I was really very focused on one character in particular, so the genre enabled me to be closely in her head, and so intimate with every kind of twist and turn that her thinking takes. And that is that being able to get that kind of subtlety lets me pin humanity in, in the mix in a way that anything more anything shorter wouldn't be able to do. Because I'd have to summarize or skip parts. And I think it's really in the details of the voicing of Victoria that her humanity is able to exist: her attempts and her struggles to understand the world and her life and her place in it. Not just the obvious things like the disappearance of her friend, but everything that's going on. And so it's the voice being given that amount of free rein, and then I think there's something about the sort of the, the way that it allows for structure. So I sort of very, very intentionally and deliberately have five parts in the book that are structured, following verse by verse, that Shakespeare song [from Twelfth Night, “When that I was and a little tiny boy (With hey, ho, the wind and the rain)”]. So that song already has that structure built into it of the five versus following different life stages of the singer. Writing a piece where voice is central to genre, then letting that voice speak for a long time, and also having that structure in it: I don't think I can't imagine doing a project like this without having those tools. There's something that I'm trying to do here that wouldn't be possible to write if I were trying to write clearly. I spend a lot of my life training to write very clear and precise academic prose in essays and monographs for a highly trained, highly specialized audience. That style is very useful, but it's almost like a precision tool. It's like creating technical drawings and using those tools to draw an impressionist painting. You just need a completely different set of approaches and tools. So the kinds of vagueness and abstraction it brings in, from writing the novel and writing in an unsettled prose, with complex and conflicted characters.

Earlier, you mentioned that there are some really rich aspects of real Cambridge that helped you develop the world-building of Victoria Sees It for you. Is the secret society Ginny invites Victoria into one of those real-life things? And if so, did the society really threaten to cast you into a pit of flame if you revealed its secrets?

Haha — I wish I could tell you, but then I'd have to cast you into a pit of flame!