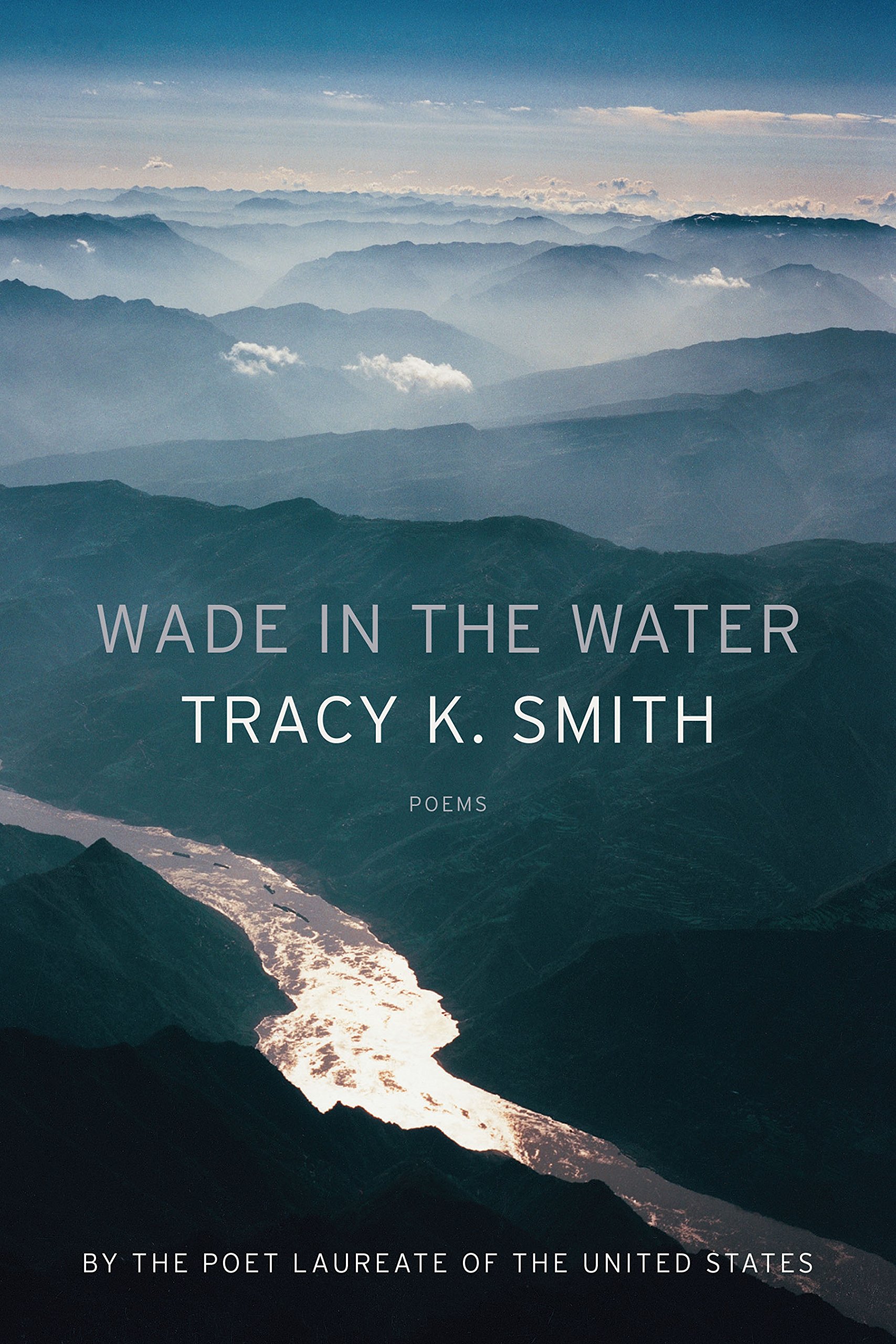

I was lucky enough to speak to poet Tracy K. Smith and listen to her read from her then-forthcoming book, Wade in the Water, when she visited Taipei in April 2018. When we spoke, she was the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the book Life on Mars, and two months away from being named the United States Poet Laureate.

I found my interview with Smith very difficult to transcribe. Not because the recording was full of it was full of

Art is trying to do something that’s fundamentally impossible, which is to find or forge a sense of clarity out of something that is finite, and muddled, and dim. Our lives, our world. It’s trying to foster some sort of revelation, some sort of realization, even though it’s momentary. It’s freezing time, so that type of thing can happen. All of that work is not ordinary. It’s not “Dear Diary, today I woke up and ate breakfast.” Art makes something worth watching.

Listening to her, it felt as if all of her words were poems waiting to be shaped. There are clearly lines of thought that she’s been dwelling on, circling in on one of those more sharply-honed emotions I might see in print two or three years later.

Our conversation, a slightly shorter version of which was previously published in

What’s one revelation that’s shaped your writing?

I went through this really awful writer’s block when I was 22—maybe 24—I was in a really competitive writers’ workshop, and with everything I submitted, it felt like there would be someone in the room who would give it back to me with a big “X” through it. At that point, I stopped bringing poems to class—because that kind of feedback hurts! I stopped writing for months, but I needed to make something, so I took a black-and-white-photography class, which became a powerful alternative to language for me. I realized that you can tell a story with images. And I learned how to look at things.

That’s what you would do, you wait for the film to develop, and you say, I took six versions of this thing, but this is the one that has feeling in it, this is the one that captures something. I realized that in every composition there are these minute gestures that have the world riding upon them, and I realized: oh, I can bring that into my poems. Instead of saying that there’s a lonely woman, I can build a picture that conveys loneliness because of what surrounds it, that has some sort of emotional weight, which frees me from having to explain. I got really excited, it really brought me back into writing, because for once I could stop struggling with what to say and just look.

In Ordinary Light, you’ve probed into incredibly vivid details of your earlier life. Was searching through those memories like looking at images, or “interviewing the self”, so to speak?

Oh, that’s interesting—there was partially an interview aspect, but overall I think I would have to call it something else. Images live in prose as well, but what I learned in writing the memoir was that I couldn’t let them do all the work. And I had to learn how to let one memory or story kind of lead me to another, and then go back, remembering smaller and smaller details, to make what I was recollecting seem a little more real.

But after that, I also went back to think about the historical context of what was going on at the time, and to try and imagine how that could become part of the story—if it had some bearing upon the events that happened or the decisions we’d made. And then another perspective was brought to bear on the material by my editor, who asked questions that made me dig deeper and realize that I had the opportunity of—this is where the interview part comes in—of almost moderating a conversation between my adult self, now that I’ve had all these experiences, and my younger self.

Oh, that’s a really cool way to put it. Did you want your memoir to be a preservation of your childhood, the little-kid Tracy K. Smith, at all?

At first it was just going to be the little kid. I wrote the book in the present tense, and in the first person, for my first draft, but that didn’t allow me to reflect on anything. It felt too thin: I needed reflection. But I also thought that my motivation wasn’t really to write about myself. I wanted to write about my mother, and about my family when we were all together in the family house. And I wanted to do that so my children would have a portrait of who who my parents were. In fact, I was almost shocked at how much of the memoir was really about myself. The interactions I had with other people were really just illuminating things about me. And then I realized, oh that’s good, because I didn’t feel right being critical of other people. But when I needed to be hard on someone, there I was in the center of the story, and I could be hard on myself.

So did you write Life on Mars and Ordinary Light knowing that they’d be tributes to people in your life?

That sense of tribute developed gradually with Life on Mars, because it was while I was writing those poems that my dad became sick. In fact, there was one section within the sequence called “The Speed of Belief”, that originally began —

I don’t want to wait on my knees

In a room made quiet by waiting.

That was the point during his illness when I knew that death was not only possible but probable. And then it happened, and that feeling of loss took over in a lot of ways. The entire book — even the poems that had been written before my father was sick — became an elegy. Almost residually, an ambient elegy.

Did you see the poems themselves shift to fit their context in any way?

I noticed different things in them. It’s kind of like how I now read my first book — back then, I was young, and I was in my first marriage, which I later got out of. I look at some of the love poems in that book, and I think, I must have known that this was going to end in divorce. I knew it but I didn’t know it. I can see the darkness at the edge of those poems. In the same way, I can see now in Life on Mars that elegy had been on my mind even before I understood that it was. A poem I remember from earlier on in the book’s making, “Motion Picture Soundtrack”, ends with:

Everything that disappears

Disappears as if returning somewhere.

I think that was a way of imagining whether it was possible to make peace with what was going to happen. You can see that now, but I didn’t back then.

What’s on your mind right now, and how do you see that reflected in your work?

My new book is called Wade in the Water, and it’s thinking about a lot of things: a lot of race, and love. There’s a found poem that is drawn from correspondence written during the Civil War, from the letters of black soldiers who were trying to claim their pension as U.S. veterans. A lot of the blacks who fought in the Civil War while enslaved and who were emancipated, didn’t have birth certificates; they didn’t have marriage licenses; they often changed their names once they were given a say in the matter. And then the government essentially said to them, We can’t pay your pension, because how can you prove to us that you are you?

That is just really heartbreaking to me. There are other historical poems that are thinking about slavery; and then there are others about the environment.

I would say that most of the poems in this book are thinking about love as a force. I’m not talking about romantic love; but love as a choice we can make about how we can regard one other. There are poems grappling with contemporary America; they’re thinking about some of the implications of not caring about each other, not wanting to stand up for one other.

I would say that most of the poems in this book are thinking about love as a force. I’m not talking about romantic love; but love as a choice we can make about how we can regard one other.

Where does the boundary lie between your identity as an activist and your identity as a writer?

Identity is interesting, because it’s real in lots of ways. My identity as a Black woman also means that a lot of the social justice questions that come up in my writing are an extension of who I am. Even if they’re about someone from around the world who doesn’t look like me. But identity can be so slippery. It shapeshifts. And sometimes we need to allow ourselves to be in control of what identity does and what we need it to do for us: that’s where you draw the line, I think.

What I love about poetry is that I get to go to a place in myself that is so me that another person’s expectations don’t apply. It means I can choose a stance in relation to the material that is true for me, regardless of whether it’s obvious or relevant for someone else.

In your poem, “They May Love All That He Has Chosen And Hate All That He Has Rejected”, from Life on Mars, you dedicate a section to writing postcards from and to different subjects, all viewed by you from the lens of current events storied. It made me wonder, how much of your activist writing is owned by your own voice, and how much of it is space you’re making for the people you’re trying to amplify?

TKS: I think that any time there’s an “I” in the poem, I have to convince myself of my connection to it. So if it is an “I”—like in those postcards—I have to imagine a proximity to those perspectives. If I am the person speaking from the poem, then I have to do the opposite—turn my own private feelings into something that has the ways and the authority of art. I’m allowing myself to become bigger than myself—sort of a small-scale mythic figure—in order to write the words. Otherwise, why would I write a poem? Why not make a phone call? I like to remind my students that we should always recognize what Emily Dickinson said: “When I state myself as representative of the verse I do not need me but a supposed self.” Even though the poems feel like they can be coming out of private experience, they’re actually something made to be heard. It’s freeing, because you can be more honest if you can assume that your reader is large enough to give you space, to be yourself. So my voice isn’t mine in the regular sense, but it doesn’t come from anyone else, either, except for this invisible authority.

Art is trying to do something that’s fundamentally impossible, which is to find or forge a sense of clarity out of something that is finite, and muddled, and dim. Our lives, our world. It’s trying to foster some sort of revelation, some sort of realization, even though it’s momentary. It’s freezing time, so that type of thing can happen. All of that work is not ordinary. It’s not “Dear Diary, today I woke up and ate breakfast.” Art makes something worth watching.

How has your personal identity shifted because of your writing?

In writing my memoir, after I had written my first draft, I was thinking about things I had left out: what had I sublimated or avoided? And one thing I realized — this strikes me now as so silly — I hadn’t realized how much I needed to talk about race. I had to go back and consciously think about the relevance of race to the material and once I started doing that, all these other things started opening up.

I knew my mother’s religious beliefs were going to be a big part of her life and her death, and I had gone to church for my whole life, but I didn’t realize I would have to do as much soul-searching of my real beliefs and my resistances to some areas of religion and what it morphed into. So that was hard, because I feel almost embarrassed—for some of the poems in Life on Mars, I go, Oh, God this and God that, but I think it was really hard as an artist, as a member of an institution of higher learning, to talk about God.

And not in an ironic way. I had to say, It’s real to me. I hate what it conjures for so many people; how am I going to consciously explore this reality? That was a long process, but I feel grateful for it, because now I understand what I believe in, how I got built.